According To Researchers Modern Leaf Blowers Have Deep Roots In Mexican Heritage And Can Be Traced To Aztec Religious Rituals

By PEDRO HIDALGO-ROMERO

The piñata. The taco. The siesta. The leaf blower. Wait a minute, the leaf blower? Yes, the leaf blower. According to at least one researcher, the leaf blower is also a part of Mexican tradition. In fact, the leaf blower likely can be traced to the pre-colonial era Mexico. Panoramic image of temples north of Mexico City.

Panoramic image of temples north of Mexico City.

With the growth of Latino horticulture in the Sun Belt states, Rosa Alonzo-Diego, Professor of Political Science and Director of the Latin American and Latino Studies Program at Sonoran College in Casa Grande, Arizona believes that Latino gardeners are using a tool that can be traced to the ancient Aztec civilization.

“I have no doubt the leaf blower can be traced to the Aztecs,” said Prof. Alonzo-Diego. According to Alonzo-Diego, the Aztecs used a pre-gasoline motor leaf blower in their sacrificial rituals.

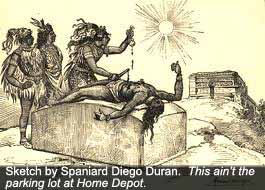

In fact, the Aztecs participated in large and well-choreographed human sacrificial rituals in worship to their gods. According to Bruce Hicks, Professor of Latino Studies at New Mexico State University, the human sacrificial ceremonies were on a magnificent scale. “The Aztecs excelled at pomp and ceremony,” said Hicks. “Nothing like these [sacrificial] ceremonies existed in Europe,” said Hicks. “In fact, at the bigger ceremonies you might have 50,000 people in attendance. That is more people than lived in all England at the time.”

At a larger ancient Aztec ceremony as many as 1,000 prisoners could be sacrificed from atop the Aztec pyramids in one day. Priests would kill prisoners by slicing their chests open using a special knife and then remove the heart muscle from the chest cavity. “The actual sacrifice would have been virtually painless for the prisoner,” said historian Hector Guadalupe-Hidalgo. “It really was nearly instantaneous, and much more humane than any ritual killing going on in Europe at the time,” said Guadalupe-Hidalgo.

At a larger ancient Aztec ceremony as many as 1,000 prisoners could be sacrificed from atop the Aztec pyramids in one day. Priests would kill prisoners by slicing their chests open using a special knife and then remove the heart muscle from the chest cavity. “The actual sacrifice would have been virtually painless for the prisoner,” said historian Hector Guadalupe-Hidalgo. “It really was nearly instantaneous, and much more humane than any ritual killing going on in Europe at the time,” said Guadalupe-Hidalgo.

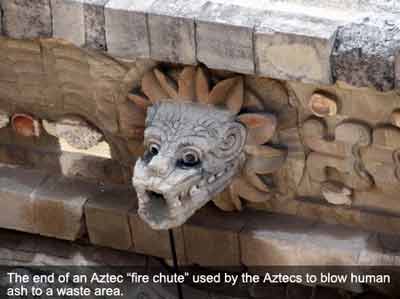

Just as in any Western religious ceremony, religious tools played a central role. Pre-Columbian museums are filled with stone alters on which priests impaled prisoners and carved their chests open. One tool, however, remained a mystery to researchers. “We just could not assign a function to the ‘fire chute.’ That was our name for it,” said Alonzo-Diego.

The “fire chute” consisted of a fire pit next to a stone channel with its aperture just above the fire pit. Alonzo-Diego believes the heat from the pit would pass through the channel and generate force through the other end of the chute. The vacuum would amplify the force to blow human ashes from Aztec crematoriums stationed next to the sacrificial sites. The breakthrough: human remains at the tail end of a Soplador de morales [Aztec for "blower of ashes"] in the temple being excavated beneath modern day Mexico City.

The “fire chute” consisted of a fire pit next to a stone channel with its aperture just above the fire pit. Alonzo-Diego believes the heat from the pit would pass through the channel and generate force through the other end of the chute. The vacuum would amplify the force to blow human ashes from Aztec crematoriums stationed next to the sacrificial sites. The breakthrough: human remains at the tail end of a Soplador de morales [Aztec for "blower of ashes"] in the temple being excavated beneath modern day Mexico City.

“It struck me as I drove to the temple to work and I saw at least 10 Mexicans – themselves descendents of the Aztecs – operating leaf blowers to clear dust from a sidewalk. That was my a-ha moment,” said Alonzo-Diego.

Analysis of debris next to other Soplador de mortales around Mexico have confirmed Alonzo-Diego’s theory. “The accumulation of bodies and ash would have been tremendous,” said Robert Schuler, professor of Meso-American Studies at Arizona State University. “It makes perfect sense that the Aztecs would use a tool like the Soplador de mortales.

Schuler also connects the Soplador de mortales to the modern Mexican love of the leaf blower. “I sometimes joke with colleagues that the official bird of Mexico is the leaf blower,” said Schuler. “The same culture that gave birth to the Soplador de mortales naturally would embrace the leaf blower.”

The next time you complain about a that infernal whirring noise outside your window, perhaps you should be aware that your neighbor’s gardener is simply celebrating a centuries old custom. You might also reflect for a moment that in another age, those leaves could have been you.